Hi — just a note as a short preamble. I wrote this piece before the death of George Floyd and the widespread response that followed, including destruction and protests not far from where I live in Seattle.

There’s a lot to absorb and reflect on. My focus, particularly as a privileged white American man, is on listening.

I’ll still be writing things and having a dialogue with you, dear reader, but for now, I’m going to hold off on the next pieces of the intuition mini-series that this piece is a part of.

One of the challenges of making decisions in this complex world is that we might not even know that our decisions are bad.

The human brain is so good at filtering out data that undermines our conclusions that we may never recognize that we could have taken a better path.

Fortunately, there’s a solution to this challenge: structure.

One broad class of strategies is to create feedback loops. We can break down a problem into more manageable bits that we can test, looking for validation of an idea and capturing feedback.

The best teams create feedback loops around their own work, reflecting on how they’re performing — and changing what they do as a result.

Reflection helps us get better over time (as do some of the strategies I wrote about here), but there’s another class of problems that they don’t work well on: when we have to make a single decision at a point in time.

Decisions like buying a house, hiring someone, or choosing a project.

Or, as it turns out, whether a patient should get an X-ray to see if a hurt ankle is sprained or broken.

For a long time, physicians diagnosing a hurt ankle were misled by symptoms that didn’t actually matter, like swelling. On the whole, they ordered many more X-rays than they needed to, using them as a sort of diagnostic safety net.

But those X-rays cost money — a lot of money when added up across everyone with an injured ankle — and exposed patients to unnecessary radiation. Doctors also missed severe fractures, skipping X-rays even when they were needed. They relied on their gut instincts, but they never got enough feedback to improve those instincts.

In the early 1990s, a team of Canadian physicians set out to change things. They ran a study to identify the factors that really mattered. The data showed that, by using only four criteria, doctors could cut the number of X-rays by a third but still catch every severe fracture.

Four simple questions turned every doctor into an expert diagnostician. They asked about pain, age, weight-bearing, and bone tenderness.

Simple and predetermined, these criteria did much better than doctors’ intuition.

The physicians had the benefit of a rigorous study, but using criteria can be powerful even without a big dataset.

Think about how we typically pick who should run an important, high-risk project. We might consider a pool of potential project managers, intuitively compare them, and then make a choice. But that would be letting our gut feelings lead us astray.

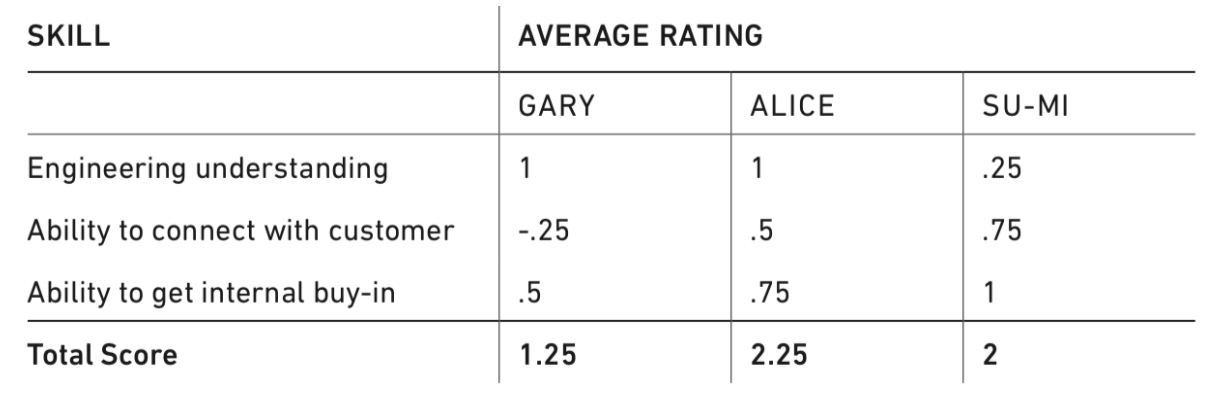

Instead, we should develop criteria based on the project. First, we determine the essential skills that the project manager will need to be successful, and what it would look like to be great, OK, or poor at those skills. Then, as we compare potential candidates, we rate them with a 1, 0, or −1 for each of those criteria.

If we’re working with a group to make the hiring decision, we can independently score each person and then average the results. This gives us a numerical representation of the overall strength of each candidate. Something like this:

I use it in my personal and professional life all the time; when writing Meltdown, in fact, my co-author András and I used it to evaluate different failures we wanted to write about.

I’ve also used it in coaching to help clients make decisions; I worked with one couple to help them choose a school for their daughter.

What big decisions are you working with? Would establishing a simple set of criteria help you move forward more confidently?

Subscribe here and join the conversation.

Parts of this post were drawn from my book Meltdown, written with András Tilcsik. Used with the permission of the publisher, Penguin Press. Copyright © 2018 by Chris Clearfield and András Tilcsik.