Updating a standard business metaphor

Fans of Jim Collins’s book Good to Great will recognize the concept of “First Who, Then What.” Take the example of Wells Fargo (well, the Wells Fargo of the 1980s, long before the inglorious fake account scandals that have plagued the modern-day bank). Instead of generating a grand strategy and getting alignment, CEO Dick Cooley hired talented executives, sometimes without having a specific role for them in mind. The idea being that we need to have talented people “on the bus” before we even set off on our journey. The right people, Collins argued, will be flexible enough to change and adapt as the destination changes.

Today, the metaphor is a bit dated. Not that we don’t need good people, but that we don’t want them on a bus!

A bus has one driver and a bunch of passengers. It has one direction and not much agility.

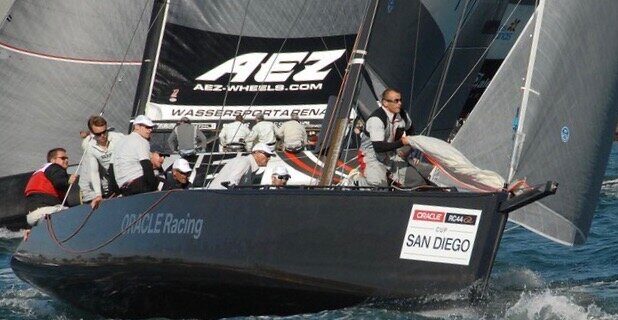

What we really need are the right people on the sailboat, which doesn’t go anywhere without people working together.

You need a captain, who is ultimately responsible for the safety and direction of the entire voyage. But you also need people that can read maps, understand weather and tides — to both watch out for risks and notice opportunities for particularly speedy progress.

You need someone who will nourish the crew (in spirit and body). You need someone who understands the technical aspects of the boat and crew members who know how to work the lines and the sheets.

And even when the destination is known, sailboats change direction all the time in order to reach it. All of this rings much more true to me than having a bunch of folks just sitting on a bus.

As a coach, I often help my clients get the right folks on their sailboats. That might mean making sure they have a skilled team working in their business, which can include the hard task of counseling underperforming employees out.

But I also like the sailboat metaphor as a lens on us as individuals.

We all have a unique combination of talents. We’ve ideally got a well-balanced sense of self that moves us forward with purpose. We’ve got parts of ourselves that are alert to both risks and opportunities. We’ve got skills, too: technical and relational. And hopefully, we have a way of taking care of ourselves and others and expressing love.

I love to help clients see all these aspects of themselves at work. Though there may be facets of ourselves that we want to change (I, for example, often wish that I could be more patient), we have to make friends with those parts because they often contain our gifts — my impatience stems from thinking and moving fast. The key is to be choiceful about how we express these things.

One of my favorite views on this comes from the Buddhist writer and teacher Pema Chödrön.

The problem is that the desire to change is fundamentally a form of aggression toward yourself. The other problem is that our hangups, unfortunately or fortunately, contain our wealth. Our neurosis and our wisdom are made out of the same material. If you throw out your neurosis, you also throw out your wisdom.

What aspects of yourself can you see as both a neurosis and a superpower?