Jim Riley had what seemed like an impossible problem.

How could he and his team of dynamic and creative teachers keep their focus on the University Cooperative School’s core mission: to help its pre-K through fifth-grade students learn without giving up the wonder of childhood.

The crux of the challenge, of course, was the global pandemic.

While online school ticked a lot of boxes, it also created massive gaps. There’s not much “wonderful” about being stuck inside a Zoom box, as I’m sure many of you have experienced.

But, more importantly, Jim and his colleagues observed that kids weren’t getting the kind of social-emotional development that was at the core of the school’s mission.

What was he supposed to do?

Jim faced the kinds of problems that many leaders I work with face: lots of moving pieces. There were numerous constraints that he needed to satisfy. The stakes were high. And there wasn’t a clear path forward.

Even as the school installed more sinks and new air filtration systems, Jim and his fellow teachers discussed how to move forward. In one of those discussions, a good idea bubbled up: starting out the fall with outdoor education.

But an idea is far from a solution.

One thing that became clear as I spoke with Jim for my podcast was how much he engaged with other stakeholders about the issue.

Complex, consequential problems require novel solutions. But novel solutions can’t be imposed. If they are, people resist—and they won’t be convinced by data.

So, Jim and his colleagues engaged. They sought out the advice of a group of physician parents who created a detailed plan for wellness-screening to help keep everyone safe from the coronavirus. Teachers packed wagons to haul their supplies around. Kids donned muddy buddies to keep them dry and insulated from the elements. And parents hacked together outdoor toilets (“fun buckets”) in portable pop-up tents that could be set up and taken down in Seattle’s public parks. (When a parent initially proposed this idea, people thought it was a joke).

Pivoting is not something that you do for fun or on a whim. It is leveraging your core skills and experience to make a shift.

To pivot successfully, you need to embrace an attitude of learning. You need to be willing to try things, experiment, and be comfortable not knowing how something will work.

That’s ultimately what Jim, his colleagues, and the entire school community embodied as they took on the challenge of outdoor learning.

I work with many leaders in big companies who face the same challenge: they have to solve a big problem with an as-yet-unknown answer.

The ones that succeed look a lot like Jim: they willingly acknowledge that, even though they don’t have the answers, they’re excited to be on their journey.

It took me years to realize that the value I provide as a consultant isn’t knowing the answers (I don’t!). The value I provide comes from my presence, from being a part of a leader’s journey as they walk their own path.

What about you? What’s an impossible problem that you’re working on?

* * *

Want to get these articles in your inbox? Subscribe here to join the conversation and download a sample from Meltdown.

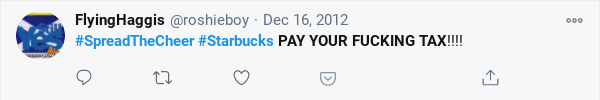

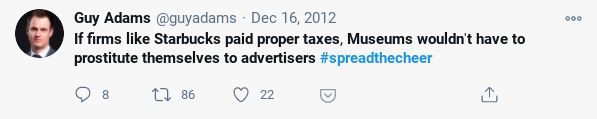

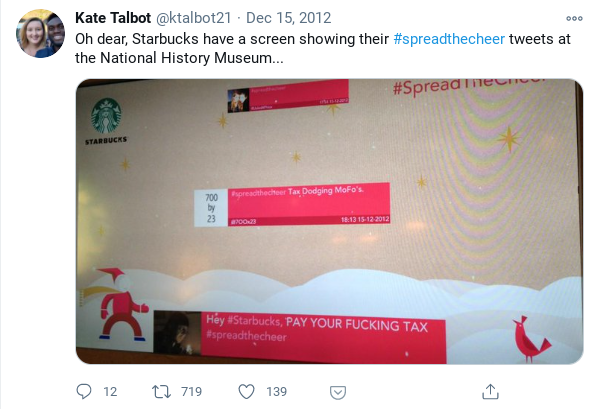

News of the ongoing fiasco spread quickly over Twitter and encouraged even more people to get involved. “Turns out a Starbucks in London is displaying on a screen any tweet with the #spreadthecheer hashtag,” one man tweeted. “Oh this will be fun.”

News of the ongoing fiasco spread quickly over Twitter and encouraged even more people to get involved. “Turns out a Starbucks in London is displaying on a screen any tweet with the #spreadthecheer hashtag,” one man tweeted. “Oh this will be fun.”

Starbucks found itself in

Starbucks found itself in