Whenever groups are at loggerheads over a decision, it makes me think that a system is involved.

Whether it’s a question of public policy or a strategy for a complex project, when I notice entrenched opposing views, I sense that we haven’t gotten to the underlying issue.

Take work like software development or a lawyer who reviews contracts. One leader, Rachel, might want to create a team to handle the work in-house, while her colleague Susan feels equally strongly that it should be outsourced.

Each can, of course, muster arguments to support their decision.

Rachel: “Handling it in-house will be higher quality!”

Susan: “It will be far cheaper if we outsource it!”

This is clearly a straw man dialogue, but it highlights something that many discussions of this type have in common: Rachel and Susan aren’t even talking to each other about the same aspect of the work. One is focused on quality, the other on cost.

Often, these kinds of discussions are resolved with a “HPPO” approach to decision-making; we fall back on the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion.

A great decision, however, draws on a deep understanding of the underlying system that highlights the real compromises — and the pseudo compromises that are actually opportunities for innovation.

So, what’s the secret to understanding a system?

It’s the superpower of curiosity. We have to prioritize being curious over being right.

That’s hard! Here are three ways to make it easier.

1. Listen deeply.

I wrote last week about the gift of listening and resting in uncertainty. This often isn’t the right strategy with a peer, but it can drive insight with your customers (who may be end users or colleagues from a different division that your solution will ultimately serve). Listening deeply can help you tease out the underlying factors that are important.

2. Combine advocacy with inquiry.

With peers, we already have a starting point for our views or experience that we can draw from. In these cases, we can combine advocacy with inquiry.

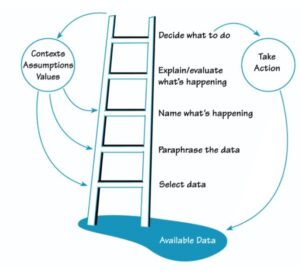

One of my favorite tools for this is Chris Argyris’s ladder of inference. Chris was a Harvard Business School professor for many years.

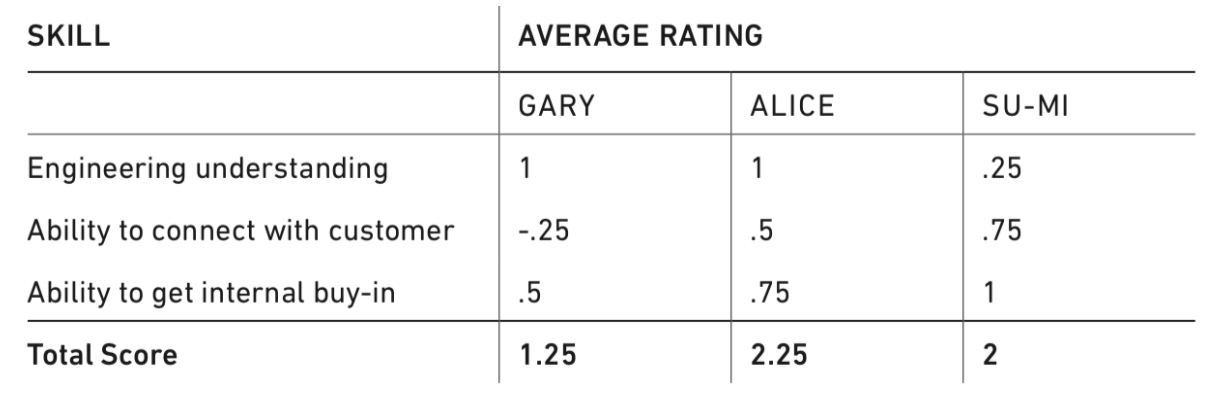

3. Add structure.

As you know, I’m a fan of structure. To unpack seemingly dichotomous choices, I like the structure that my friends Roger Martin and Jennifer Riel developed in their book Creating Great Choices.

The CGC framework helps teams flesh out the benefits of extreme positions (outsource everything vs. bring all work in-house, for instance) to see the underlying benefit of each option.

In articulating the underlying jobs that the models do, we can see if there are ways of combining them into a third, integrated solution. It might be that we triage our contract work to outsource most contracts, but send important ones to an in-house specialist. In a software context, we might use outsourced developers, but integrate them into our sprint process as if they were in-house.

Roger and Jennifer’s framework is particularly useful for articulating bigger strategy decisions. It’s on my mind right now because I’m using it with a group who’s trying to decide what parts of their service should be centrally controlled vs. delegated to business units within their large organization.

That’s three approaches to understanding a system — but there are many more. What are the skills you use to deepen your understanding?