Practical tips to avoid change management screw ups

We’ve all been part of boneheaded changes in our work. Somebody gets an idea about how things could be better, and, all of a sudden, we’re using a new piece of software, emailing weekly status updates to our manager, or wasting time filling out those dreaded TPS reports.

Many of these changes are dumb. Full stop.

That’s because, in most cases, the ideas come from people who don’t really understand the problem. Managers reach for control to tame uncertainty (even though that’s actually what they need to embrace).

Even people who understand the problem may not get the solution right. They come up with something that works but only in a specific context.

As a result, people resist the changes.

People resist good changes, too. It’s only natural. Humans value autonomy and security and being told to change threatens both of those things.

Right now, I’m working on two big projects — one with a group changing how Microsoft consumes and delivers all things legal, one with another Fortune 10 firm — where I help leaders use curiosity to accelerate transformational change. We spend a lot of time talking about resistance, about the importance of getting everyone to understand the “why” of a change, and about the details — from who needs to be involved to how we plan meetings with stakeholders. (Quick tip for meetings: try to limit any presentation about change to five slides and, instead of presenting data, ask people how they’re feeling).

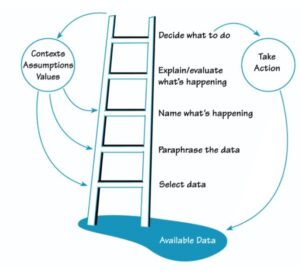

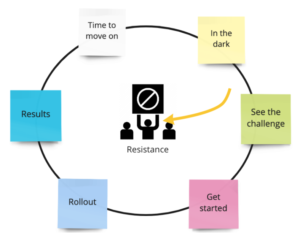

One of the models I use when I consult with companies is the cycle of change, developed by Rick Maurer. We use the tool to understand where different stakeholders and individuals are on the change journey. And it all starts with seeing the need for a change.

Credit: Rick Maurer

Credit: Rick Maurer

I find it delightfully ironic that I was recently in the process of flubbing a change inside my own firm.

I made all the classic mistakes that leaders make. I assumed that it was a small change. I assumed that the reasons for it were obvious. I assumed, basically, that people wouldn’t care about it.

For context: I want to change how we track the hours that people spend on different projects, so that I can better steward the company’s resources and understand the return on investment we receive from different projects, such as the mailing list, the (teaser alert) podcast we’re launching in a month, the marketing for my one-on-one coaching work, and the consulting work.

To me, it seemed like a very straightforward change.

It was my executive assistant who clued me in to the fact that I was missing something. She was concerned that the way we paid people would change under the new system. To me, that seemed like an unrelated matter — but it made me realize that I was pushing forward on a change without understanding the concerns of the people who will be affected by it.

So, I changed course by doing a few simple things:

1. I raised my awareness. I realized that while I was ready to roll out the change, I hadn’t spent time sharing the why. I had no idea whether my team even knew that there was a problem to solve.

2. I communicated. (To go meta for a second, this post is actually part of that communication. Some of the team will help get it out the door, and I’ll send it to everyone after it’s finished.)

3. I made a short video talking about the reason I saw a need for the change. In the video, I asked the team to think about what was working with the setup that we have now so that we make sure that any solution meets their needs, too. (The video is very “inside the sausage factory,” but I’m sharing it in case it’s useful.)

4. I set aside time for us to talk about it as a group. These things only took a few minutes and they are super simple. But that doesn’t mean that they are easy. Far too often, even thoughtful and well-intentioned managers (like me!) charge ahead without understanding the ripple effects of change.

For my part, my hope is that sharing my reasoning and opening up the conversation will help my team and me create an effective solution that works for them — and meets my needs to understand how we’re using resources. A small shift like this can make all the difference.

Are you working with any colleagues on change? If so, share this article with them because they might find it helpful!