Maybe you’re not in a position to lose $900,000,000 for your company.

But, if you’re like most leaders, you don’t know all the ways in which the things you’re responsible for can go drastically wrong.

Even if you’re very good at your job.

Even if you’ve been at your company for a long time.

Even if you know the technical ins and outs of the business.

Good leaders know the limitations of their knowledge. They have what I like to call “objective curiosity” about their work and their systems. They’re asking about what might go wrong, sure. But they’re also asking about how things work. They’re continually refining their mental models of the work that they’re responsible for.

It’s dangerous not to.

If you need convincing, take this story from Citibank as a cautionary tale.

In 2016, an operations group at Citi in charge of managing payments for loans—the bread and butter of finance—accidentally wired some money outside of the bank.

And by “some money,” I mean $900,000,000.

The story is almost comical in its complexity (my favorite finance writer, Matt Levine, dissects some of the high points).

The transaction itself was complex, involving the refinancing of a large commercial loan. Some lenders were participating in the new loan, some were not.

As a result, Citi didn’t actually need to wire any money [1]—but, because of the way their systems were set up, they couldn’t facilitate their client’s loan transaction without at least pretending to wire a bunch of money.

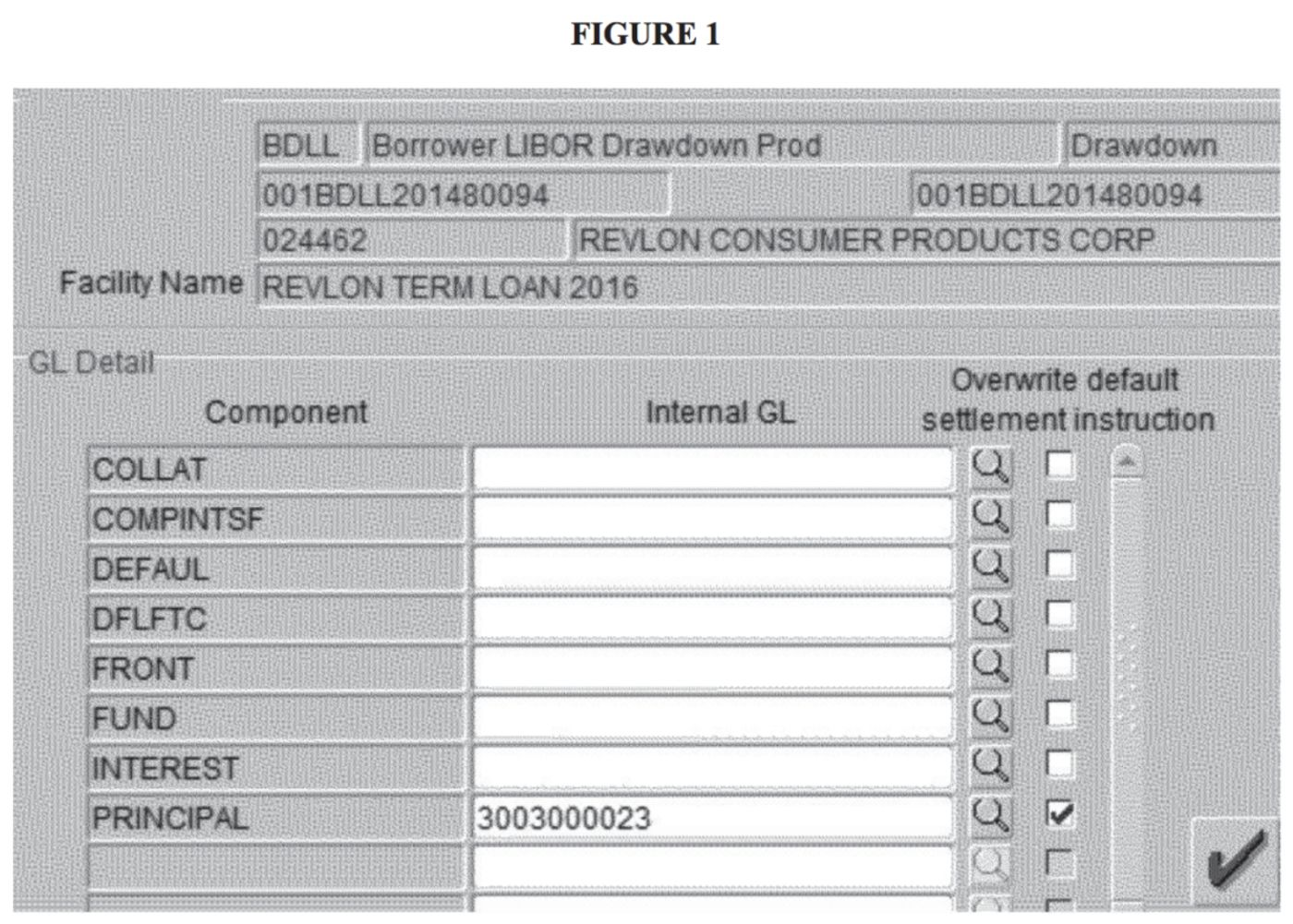

So, there was a work-around. The operations group handling the transaction could create an override by wiring the funds to an internal Citi account, instead. All they had to do was check a box and put in the number of the internal account (called a wash account because the transaction washes out). The operations person who created the transaction did that. He got two others to look at it (a “six-eye review process”). It looked good to everybody, so they put the transaction through.

The next day, operators realized that they had incorrectly wired out nearly a billion dollars.

As it turns out, they understood the transaction, but they misunderstood their systems. They had put in an override. They checked the override in the “PRINCIPAL” box and put in the number of the wash account.

But, as Levine reported, they needed to check three boxes:

[The manual] explains that, in order to suppress payment of a principal amount, “ALL of the below field[s] must be set to the wash account: FRONT[;] FUND[; and] PRINCIPAL”—meaning that the employee had to check all three of those boxes and input the wash account number into the relevant fields.

Whoops.

It’s tempting to blame the operations folks, isn’t it? But we’re not going to do that. The operators were doing their best in the system they were in. To really learn from something like this… you have to believe that you might have made the same mistake in their shoes.

This example from Citi highlights three specific lessons that can help you in any complex project or work setting. You need to be sensitive to the strengths and limitations of your people, develop awareness of how your processes really work, and seek out the unvarnished truth so you don’t ignore important issues:

Trust humans—but expect them to make mistakes.

We cannot expect humans to be perfect. We all make mistakes. And we will miss the mistakes others make.

So, you can’t just add more checks. You can’t just add more instructions.

Instead… add transparency to the system.

Generate a big, screaming graphic that shows that $900,000,000 will be wired out of your bank.

Use a Sharpie to put a big “X” on the side of the patient where you will operate.

Create a system that says “Pull up, pull up, pull up” when you are about to fly into the ground.

Make blindingly obvious what is happening—so it’s easy to see and correct.

Pay attention to work-arounds.

Safety experts talk a lot about the gaps between “work as imagined,” “work as prescribed,” and “work as done.”

Work as imagined: Managers get together in a conference room for hours of discussion about how something should work.

Work as prescribed: Managers then write a procedure (or maybe external consultants do) to tell operators how the work should actually be done.

Work as done: That procedure is given to a new group of people. These folks aren’t in a conference room. They don’t always have the right tools, the right resources, the right information, or the right amount of time. But they’re expected to do the work! And, mostly, they do.

But there are gaps—gaps that require operators to skillfully “work around” the constraints of the system and the work as it has been designed.

These gaps are an inevitable part of operating in a complex system.

Good leaders realize this. They create feedback loops to understand what’s actually being done. They listen to operators. They learn and adapt, closing those gaps over time.

But what happened at Citi was a bit different. The procedure itself was a work-around for a fundamentally flawed system. It was far too complex. It wasn’t logical. And there were few checks for when things went wrong.

Instead of accepting work-arounds… pay attention to the places where you’ve made them a part of your system. They point to places where complexity can cause failure.

Ignore them at your peril.

Seek out what’s not working.

I’m willing to bet that Citi’s system was not a topic of conversation among its senior leadership.

Why not? Obviously, it could cost them hundreds of millions of dollars.

Many organizations deal with (and ignore) systems like this all the time.

That’s dangerous. Beyond being a source of risk, I’m willing to bet that Citi’s system was an impediment to agility, innovation, and competitiveness.

I don’t know for sure. But I’m guessing that even leaders who had operational experience and deep knowledge of the business accepted the terrible system as just part of “how we do things.”

Instead… good leaders seek out the unvarnished truth about their systems. They need to know what works and what doesn’t. And they have two sources of information they rely on to know what needs to be fixed:

-

Their teams: By creating a psychologically safe environment—one where people feel encouraged to share their true thoughts and feelings—leaders can learn about underlying problems and start to work on them.

-

Outsiders: Part of the challenge of running a complex system is normalization of deviance, or comfort with increasingly risky setups. Outsiders can point out blind spots in your operations (“Wait, what? How does your system work… that’s kind of nuts!”).

Outsiders can also help you see the idiosyncrasies of how you operate as a team—the assumptions you make. The way you talk to each other. The presence or absence of hierarchy. A skilled outsider can help you see your strengths and your opportunities for growth.

Are you a leader who works in a complex system? Book a free 15-minute call with me if you’d like to talk with an interested outsider.

[1]This isn’t quite true—they needed to wire around $7 million for some accrued interest. But not the $900 million of outstanding principal that they had to “trick” their system with.

* * *

Want to get these articles in your inbox? Subscribe here to join the conversation and download a sample from Meltdown.