I think the answer is yes. But I’m not confident. Perhaps you, dear reader, can help?

Here’s the background: last week, I took my kids and dog to a swimming hole about 50 miles east of Seattle.

When we parked and got out of the car, the air crackled with electricity. We were right under high-voltage power lines.

Really high voltage power lines, as it turned out: 115 kV (kilovolts), a thousand times more than what’s in our houses.

But I didn’t think much about it.

We hung out for a couple of hours, playing in the water and digging in the sand. (We didn’t actually swim; it was too cold for that!)

As I loaded my kiddos into the car, I noticed that the car had an electrical charge. When I touched the metal post that the door latches on to (which is, presumably, connected to the frame itself), I could feel the current running through me… it was eerie.

A little disconcerting, but also interesting. I thought enough about it to google it right then and there.

I found a few message boards with farmers writing about equipment dying under power lines. But others called it apocryphal.

I found a fancy pamphlet from a nearby power authority about safely living and working under power lines. Take a look:

Shocks are caused by a voltage induced from the power line into the nearby metallic objects….

The severity of nuisance shocks can vary in sensation from something similar to a shock you might receive when you cross a carpet and then touch a door knob to touching the spark-plug ignition wires on your lawnmower or car. The nuisance shock, however, would be continuous as long as you are touching the metallic object. Such objects include vehicles, fences, metal buildings or roofs and irrigation systems that are near the line or parallel the line for some distance.

That pretty much described my situation to a T.

As current flows through the power lines, it generates a magnetic field. That magnetic field changes as the current changes (as more or less power is carried in the lines). It’s that changing magnetic field that generated a corresponding electrical field in my car. It’s physics 15B (or at least it was when I was an undergrad).

Mystery solved to my satisfaction, we drove back to Seattle.

But wait, there’s more….

Two days later, the battery light in my car began to flicker as I drove home from the park. The next day, the car died right after I started it.

The weird confluence of circumstances made me feel like I was on Car Talk. My guess was that there was something wrong with the charging system.

I asked my co-parent to give me a jump; she did and stuck around for a half hour, so my battery could charge. Right afterward, I drove to the shop and arrived with a bit of energy to spare, as the car wouldn’t start for the mechanic when he tried to drive it into the bay.

Sure enough, they had to replace the alternator (which is responsible for charging the battery).

But when I proposed my theory to the mechanic, he looked at me like I was crazy, saying “I’ve never heard of something like that happening.”

Am I crazy?

The truth is, I don’t know.

In my mental model, my explanation is, of course, right!

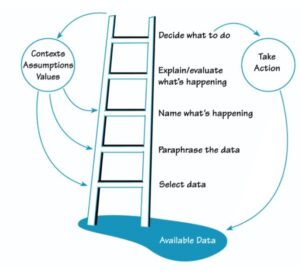

But when I hold wild beliefs, I love to return to one of my favorite tools, the Ladder of Inference.

I’ve written about the ladder in earlier posts. It’s a tool to help us check our understanding with ourselves and others.

It moves the process of evaluating our beliefs from an implicit one to an explicit one.

In this case, let’s see what I did:

First, I already selected the data to the event that is salient to me: parking under the power lines. I didn’t share other things, like the fact that I jumped someone else’s car a few days before I parked under the power lines. There certainly could have been events that I didn’t know about (such as internal wear on the alternator) that played a role. And, during my internet “research,” I spent more time engaging with stories that supported my theory (a farmer describing a drained battery after parking beneath a powerline) than those that didn’t (posts declaring that “I’ve never seen anything like that.”).

There wasn’t a lot of paraphrasing, because I was dealing with fairly binary things (battery drains) rather than with the nuance of human communication. But there were some:

-

The rawest “output” data I have is that the battery light came on while I was driving and then, the next day, the car didn’t start. I did a little paraphrasing from those observations to “There’s some kind of problem with the electrical system.”

-

I also looked for other data to support (or debunk) my theory. I drove approximately 60 miles after parking under the power lines before my car died; Quora says that cars can drive 50 to 100 miles without an alternator.

-

I also paraphrased data from other sources, like the manual from the power company.

Beyond that, I named what happened. I have a mental model of how the car’s electrical system works, so I further extrapolated to: “There’s a problem with the charging system.”

In all this, I applied some context: namely, my training in physics, engineering, and aviation. That’s where I got my mental model of the car’s electrical system. My mental model also makes it easy (perhaps too easy?) for me to see a connection between the power lines and the dead alternator.

With that context comes my explanation: when I parked the car under the power lines, it affected my electrical system.

So, I decided a couple of things. I decided not to ask just for a jump but instead to ask for 30 minutes of charging from another car. And I decided to take the car into the shop where, indeed, they found a bad alternator.

Now, of course, almost none of these decisions were explicit. I didn’t write down any steps; I quickly and implicitly formed beliefs — among them the totally unsubstantiated conclusion that parking below the high voltage power lines fried my alternator.

That’s the value of the Ladder of Inference, though. Suppose my mechanic and I really needed to come to some kind of agreement. By both of us making our thinking explicit at each rung of the ladder, we’d be more likely to have a productive conversation. “Here is the data that I am seeing. What are you seeing?”

By making our beliefs explicit as we move up the ladder, we can slowly build a shared mental model, one that drives alignment and common understanding. And when we find disagreements along the way, we can do more research and devise little tests to see if we can suss out which person’s perspective is more likely to match reality.

Here’s an exercise: take something that’s come up for you recently — at work or at home. A disagreement with a colleague or family member, say, or a tough decision at work.

See if you can use the ladder to make the climb to your beliefs (and your decision) explicit.

Let me know what you find.

P.S. Ultimately, of course, the mechanic wins either way by collecting my $723 for fixing the alternator.